This post appeared in Italian on wired.it. This is the secon part of a (poor) English translation. First part is here

Not only the food is continuously monitored: also construction wood from the forests of

the region is controlled. In this case too the safety limits are much more

severe than that of the volcanic pozzolans often used in the construction

of houses and Italian schools.

|

| Comparison between radiation Italy (Rome) and Japan (Tokyo and Saitama). It is possible to see how radioactive background is higher in Rome than Tokyo. In Rome the radiation environment is dominated by the peaks of Radon 222. The arrow indicates where the Cesium 137 (660 keV) peak should be located. |

An estimation of the amount of Cesium in food, wood or forage

requires a spectrometer capable of determining the energy of each gamma ray.

Since each isotope emits gamma rays of specific energies, it is possible to

determine the quantities of the various isotopes present.

Among the recent devices there is a

portable detector consisting of a crystal to stop the gamma (CsI) and a Silicon Photomultiplier (MMPC or

as they call them) to detect the energy measuring the light emitted in the

crystal. The simplicity of this type of tools is that they do not require high

voltages, are small as a pack of cigarettes and is used as a

USB device. The cost, however, is about 20 times that of a Geiger counter.

A spectrometer can count, for each decay, the energy of the rays

that strike it. In about an hour and then it is possible to obtain a spectrum which

describes the type and amount of environmental radiation. To improve the

statistics and better highlight the peaks is, however, advisable to wait a

while longer. The picture above shows the value measured at Rome in an

apartment on the fourth floor: it is 0.25microSv/hour (with peaks of 0.35).

In the figure above it is possible to see how

the spectrum in Rome (and in much of Italy) is dominated by radon 222, a noble

gas source to the high amount of environmental radiation. Usually the radon

comes from the soil and tuff, but in this case, since it is an apartment on the

fourth floor, is more likely to come from pozzolana used in the construction

materials . In figure are compared the spectra taken in Rome with those acquired in Japan. The value of Rome is higher (0.25microSv / h), followed by the

basement workshops of Tor Vergata (0.10 microSv / h, where, however, there is

much radon), Kokubunji (0.05), and the fourth floor in Wako (0035 microSv / h).

Note the almost total absence of radon in Japan. It is worth mentioning that

the environmental radiation at the onsen baths is higher due to the volcanic

nature of the sulphurous waters.

| Monitoring radiation in wood to be used for construction |

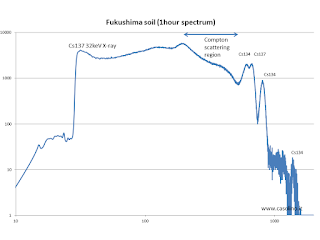

In the samples collected in the hot

spots, Cesium-137 is present in large quantities: this isotope decays into an

excited state of barium (emitting an electron and an antineutrino). The

de-excitation of barium emits a signal characteristic of this element: a gamma

ray energy of 660 keV. The process is similar to that of fluorescence, only

that in this case atomic electrons are excited. The return to the ground state

emits light (between 2 and 3 eV), e.g. electromagnetic radiation. The energy

levels in the nucleus are thousands of times more intense and therefore the

electromagnetic radiation emitted has an frequency and associated energy

thousands of times greater.

To the left of the peak there

is the so-called 'Compton edge', produced by gamma rays hitting an atomic

electron of the Cesium crystal in the detector and accelerating it with a

slightly lower energy (depending on the angle with which it is emitted). The

spectroscopic analysis of a particularly contaminated sample, taken on the side of a mountain road between the city

of Fukushima and the coast. This sample shows the presence of the isotope

cesium-134, which decays into barium with several peaks at 600, 790, 1400 and

1600 keV (the latter is out of range of the detector).

The cesium-134 has a decay time of

two years, therefore the presence of this isotope represents the

"signature" of the origin of the Fukushima power plant. In other cases, the

absence of cesium-134 was used to show how well mushrooms that had radioactivity

above the threshold of 100 Bq / kg were not contaminated by the panel, but

presumably from nuclear tests in the ‘60s.

|

| Gamma spectrum from a pure Cs 137 source |

|

| Spectrum of a sample of soil containing cesium 134 and 137 of Fukushima region |

The measures in the region of

Fukushima were extremely interesting, but equally important on a personal level

was the contact with the local population. Far from being disheartened, the people

in Tohokoku did not give up and have rebuilt many of the structures destroyed

by the tsunami. Although the plant has not resulted in deaths due to radiation

(morbidly sought by national and international journalists), many deaths are

due to poor management of the emergency in the first frantic days after the

earthquake. Others are due to suicides after resettlement. The inhabitants of

the regions closer to the center have been forcefully moved away and are now

rebuilding the social fabric elsewhere, so sometimes it is difficult to return

to their town of origin, even if it were decontaminated. The most relevant problem

is economic: the damage to the primary sector and tourism are visible to all

and will require years to get back to normal.

2. end First part is here